1

Queer French philosophers were right, ‘mental illness’ is largely a social construct. Generations prior attributed insanity to possession or otherwise viewed deviants through a religiously prescribed conceptual field. It doesn’t particularly matter that we’re now better informed of the genetic foundations of mental illness. Too many layers of abstraction are stuck between a person’s genetic substrate and the emergent property labeled a ‘mental illness’ that our image of a raw, mess of madman passes through before it hits your brain and you realize he’s trying to stab you in the neck. (Hey, I never said social constructs aren’t useful). We may as well posit a genetic predisposition toward demonic possession. Is this incoherent? Don’t know, I’m not a theologian, but we usually iron out the details ex post.

Criminality as a concept suffers from a similar dilemma. No, this isn’t to be interpreted as moral nihilism. Criminality is always defined in opposition to the Law, another realm of the human experience that hinges on a religiously imparted moral framework (hence the confusion from first-year grad students the world over between ‘normative’ as legal and ‘normative’ as moral). A society with a singular, or at least integrated, religious tradition has little problem identifying its criminal elements because there is an intersubjective understanding of what contravenes the normative rules around which the Law is built.

Our problem is ‘criminality’, as we mean it today, is a fully secularized notion detached from its religious grounding; its relation to violation of a normative (re: religio-moral) order is identical to the relation between mental illness and demonic possession. Law has spun away from the undifferentiated collective unconscious just as much as psychiatry. It, and the ‘criminality’ that mutually constitutes it, is wholly ‘scientific.’ Often this happens slowly, then all at once because the process touches the central crimes— murder, rape, etc.— last. But I suspect for any readers here I do not need to point out the obvious examples where even the intersubjective understanding of what qualifies as ‘murder’ (as in, deliberate killing of another human) has cracked. My conscience would rest perfectly fine responding to preschool drag queen bump-and-grind story-time with a Mozambique drill. In some cultures, such events are simply known as ‘the weekend.’ (And yes, to the one guy who requires symmetry for his conscience, the same applies to funny Priests). It is obvious that moral rules governing ‘murder’ also vary quite extensively, in some cultures to preclude, for instance, what we refer to as ‘honor killings.’ Self-defense as a justification for murder is not a rational law you derived with propositional calculus; it is first a moral law that was later transcribed into formal language. Don’t be surprised when people who first read about the Bible in a Sam Harris book try to game-tree the right to self-defense away.

Anne, frankly, I no longer care what other offensive moral rules people in Afghanistan or Cambodia follow to govern rape or murder. (In my moral universe Holocaust jokes are still funny; suck it). This isn’t a confession of moral relativism, which is nonsensical because it abstracts the ‘subject’ away from any context that would define him. My morals are right, because from my perspective (which arrives in large part from outside me) they are right. I can recognize that from other cultural perspectives an antithetical moral framework is understood to be correct (even if I know it to be wrong, because . . . ad infinitum). My point here is that Law, when it becomes detached from its moral foundation, is subject to drift in confrontation with outside systems; light bends to water, it is inevitable. And for the past several decades the West has tried an experiment called ‘multiculturalism.’ Oh.

Not uncommonly now I run across a Twitter argument that concludes with the claim that conservatives, or ‘trads’, ought to welcome multiculturalism because traditional values are more strongly held among third-world immigrants. This is either grave stupidity or artifice (of the ‘this argument wouldn’t work on me but perhaps if I use it against you then you’ll do what I want’ variety). Traditions are products of local, self-contained worlds with unique cultural genealogies. It is true they are subject to constant evolution, revision, and collision, but humans are stuck inside this process and are only painfully assimilated to entirely new cultural modes. And it’s all too easy to treat the abstract similarities of traditional cultures at the level of the broadest human institutions— the other culture’s love of family, religiosity, thrift, whatever— as kinship. All this means is, unlike the revolutionarily inclined, that they are not characterized by nihilism (which here would lead to contradiction). What family, religion, nation mean— how those broad institutions are instantiated— in other traditions is entirely different. I am all for good shitpoasting, but no native-born American is actually the Taliban. I triple dare you to beat the crap out your wife while your kids are strapped to a chair like they’re getting the Ludovico treatment. (Feel like this deserves a disclaimer for the occasional psychotic).

Nietzsche is an intellectual forerunner of much of the contemporary right and the postmodernists because he spiritually precedes both. He admires, or observes with dispassionate understanding, distant cultures because he sees in their internal development a process that follows the same trajectory as the ones he loves: a few great men are born within a unique cultural sphere who then serve its sleepwalkers as exemplars, a set of floating cultural signifiers whose idealized examples constitute a unique model for life. Built into this ‘perspectivism’ is acknowledgment that from within alternative cultural systems the ‘life-model’ it imparts is ‘true’ or exceptional, along with a cross-cultural disdain for the resentful who would fashion revolutionary moral systems through moral inversion. But that’s where the affinity ends, as a detente among cultures that might admire each other from a distance so long as there’s no encroachment. It’s very easy to read into Nietzsche— or Schopenhauer, or Hesse, as I mentioned in my first weekly post— a kind of cultural syncretism, but that’s the result of a certain form of nihilism that makes one’s own cultural genealogy impotent. I wonder who might have written about this?

Now that you’ve assimilated the implied paragraphs, what follows possession, mental illness, and criminality (by the last I again mean our current understanding of what that label refers to; some overlap in time exists because the social world turns quickly while we sleep: see, normiecons)? We could begrudgingly tolerate elevate homicide rates for a while, which we are already doing and is perhaps an inevitable segue into new paradigms for institutionalization. It does become increasingly hard to converge on shared moral solutions under multiculturalism: from some perspectives, ‘he done looked at me funny’ and ‘my daughter flirted with an infidel’ are perfectly legitimate grounds for homicide, as legitimate as my right to self-defense. Criminality as the highest-order abstraction— we can agree upon this more than socially constructed notions of madness— are breaking down. More generalization runs against natural limits, for every sane man knows there are exceptions when taking another life is justified and those would get scraped too under a new regime. But a new paradigm will come, I just haven’t thought about what it might be yet.

2

After trashing International Relations last week, someone recommended I read Bear Braumoeller’s Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age. I did, since it has been sitting on my shelf for a while now. It’s a rebuttal of the ‘decline of war’ thesis, made popular in Steven “don’t post that pic of me and Epstein or I’ll block you and sad-jerk in the corner” Pinker’s book The Better Angles of Our Nature and related Angellites. And “haha, no, seriously, don’t look on my hard drive” Pinker is merely the thesis’ most popular advocate; the idea of a ‘decline of war’ or ‘long peace’ has been the dominant view for several decades among international relations scholars, especially the quantitative ones (who tend to refer to themselves as ‘peace researchers’, as distinct from the older, qualitative ‘security studies’ scholars who were preoccupied with little things like great power war and nuclear weapons).

I have a number of reservations about the book but I’ll put them aside because the author is relatively honest and humble regarding its shortcomings. It excels at its principal objective: to demonstrate that the decline of war thesis is not supported by the evidence. It does this with a set of remarkably simple tools: basic probability theory, logic, data visualization, and a few rudimentary statistical hypothesis tests. The results are solid— it turns out that what we’ve observed as the recent ‘decline of war’ is perfectly consistent with the longer historical trends (i.e., it’s likely to have occurred by chance). If anything, the book shows that the decline of war thesis is precisely backwards and that warfare has increased over time (however measured, either in number of wars, battle deaths, or deaths over global population).

Obviously— wherever you stand on the debate, as I don’t particularly care— this is relevant to the ongoing war in Ukraine. A difficulty, one illustrated quite nicely in several of the book’s historical vignettes, is that it’s impossible to know ex ante which wars will escalate into globally catastrophic ones. Each interstate war is basically a roll of the die when it comes to the eventual scope and severity of the conflict, even if we can invent soothing narratives as to why such-and-such a war was certainly destined to fizzle out without much fanfare after the fact. A cautious attitude toward war is advisable on those grounds alone, though from my recollection it’s a consideration that seldom enters into the writings of statesmen. Perhaps the ‘rationalist explanations for war’, like information asymmetry, formalized what were actually psychological causes all along, and the main psychological cause is, as always, severe mental deficiency.

Again, it’s remarkable the author demonstrates the ‘decline of war’ thesis simply does not follow from basic probability and logic. Why, then, did nearly the entire sub-discipline of quantitative international relations not reach the same conclusion? The absolute honest reason: they’re morons. Most political scientists enter graduate programs with little to no training in mathematics (myself included, to be transparent). The training to become a ‘quantitative political scientist’ does not rectify this. Mostly the curriculum involves several of the easier econometrics textbooks and then progression to more specialized courses that survey ‘political methodology’ articles in some domain (e.g., causal inference, survey research, how to use ggplot so you can make figures without crying). I have never seen a single graduate level political science course that assigned the books Statistical Inference or All of Statistics, which really ought to be the bare minimum. And the professors are so delusional I have never seen one, not a single one, think they might lack the foundations to do or understand quantitative analysis. They do plenty of canned regressions on war and peace, but almost none thought about the underlying probability distributions; the thought could scarcely occur to most of them (‘uh, hey, that’s not true, maybe wars are Poisson distributed (I remember reading that word in a paper (well, I remember reading that in Gravity’s Rainbow, we are not the same)), or something’). So remember, when a quantitative political scientist tries to disarm you with ‘the literature’ that it doesn’t amount to anything at all and there’s a high chance they’d fail an entry-level data science job interview. That’s not hyperbole; I’ve seen it happen multiple times first-hand. Well, that’s not entirely true; many of the younger generation have been quick to pick up on the horror of their predecessors’ work (but they’re all running for the hills in industry— who gets stuck behind in the Ivory Tower? At least they’re better read on history, then. Right?)

Anyway, it’s a decent read. None of this was particularly new to me, since all the conclusions are easy to arrive at if you’ve thought about the problem for any non-trivial length of time and you have a brain. It’s worth skimming if your only exposure to the decline of war thesis is “no, I don’t hear any sounds coming from the basement” Pinker and you’ve (correctly) intuited something’s amiss. Foreign policy elites should read it too, although it was published only three years ago so perhaps it will take some time. If we’re lucky they’ll even read it in time.

3

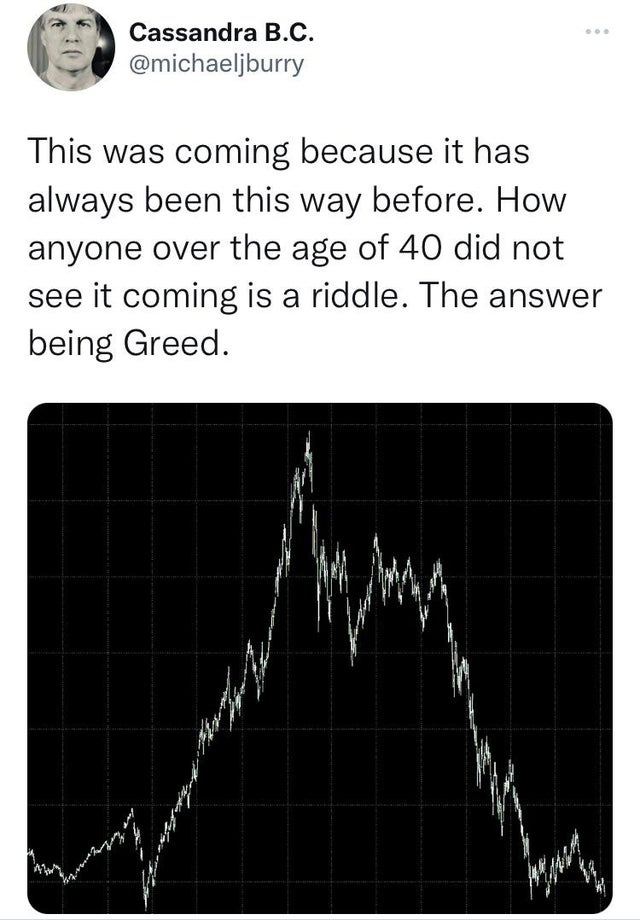

More from the Big Autist— chart is 3-year ARK Innovation ETF. I believe he’s discounting stupidity here because this may have been the most predictable event in the history of capitalism. (If I had enough liquidity to play with options more and not have to worry about accumulating long positions for the next decade I’d be a billionaire now). It looks like the S&P is following suit. Yet, to me it pays to be nimble; I’d rather lock in short-term gains so I can pretend to sleep well at night. I closed my largest long volatility position this week since it’s difficult to time rallies, even if this counteracts the benefit of the low-probability event of capturing ridiculous asymmetric gains (invert the normal rules mid-way through a bear market, I say).

I also closed short positions in Duolingo, Crowdstrike, SentinelOne, Snowflake, Li Auto, and Paylocity for between 10 and 15 percent this week. Maybe they will really tank next week, but I suspect for most a volatile slide is still likeliest and there will be opportunity to play again (already I’ve shorted Duolingo five times— even with a decent balance sheet it’s a worthless company, although by swing trading smaller positions I won’t get hammered if some poor mega-cap decides to buy it out and teach people how to say, “downdey estar el banjo?” in the Spanish metaverse).

One of the biggest headaches in a bear market is having to swing trade what would otherwise be viable long positions due to the volatility. Normally I prefer to accumulate them over at least a year and target 35 to 50 percent gains on a single position, but like everyone else I find these positions gets destroyed quickly so it makes sense to capture gains and re-allocate the cash whenever possible. That eats up a lot of time in research alone. Coda is a cool underwater tech company (no, not like that— you’re a few decades early) that I would have liked to accumulate a 10k+ position in before exiting but it’s impossible to tell whether it will revert quickly. Now I have to contemplate where to allocate a bunch of closed 1-3k positions and, with these, it’s tempting to just let my cash pile grow, which is unwise since it will get decimated in inflation. (This is the second reason I am not recommending many individual stock purchases— that would assume agility in trading that I can’t comment on in real time. The first reason is that I’m retarded).

Even with the painful cost (in time) investment, I plan to continue trading quite actively for the foreseeable future. It’s saved me this year (which, if I continue on track, will be my fourth ~30% year in a row (my first year was a painful -45%, if that makes you feel better)), where I hear much wailing and gnashing of teeth. But a greater concern motivates my active investment. The chart below is the inflation-adjusted S&P 500 index between 1964 and 1984. Now, do you really want to passively drop your money into an index in this scenario? That’s twenty years— the majority of your working life, ages 30 to 50 with minimal returns. And sure, if there’s a satisfying climb around year 25 perhaps you’ll be fine, even decently well-off, although after a couple years of mediocre returns at the beginning it’s likely you would have only allotted the minimum (401k and IRA max comes out, I believe, to 25k. Do it, if that’s what you can spare, but it’s terribly insufficient if you’re making good money).

Who knows whether a similarly flat decade will follow our current downslide? I have no idea. But I have noticed this: even with all the wailing and damnation of the great market hexagrams and astrological signs, almost nobody has yet to question the dogma— and it is just that, not a scientific law— of passive investment. If it falls, it will be last among the idols. And when the whole world unthinkingly buys into a strategy, that’s usually when it begins to fail. I admit it’s a terrible pain in the ass to take responsibility for all your decisions, but in uncertain times that’s the best option. It’s an especially good option when nobody else seems prepared for the work involved. What kind of world do you think we live in today?

On that note, this morning the Autist also shared this commentary. Read it. We have entered into a new structural period in the global economy due to— and, honestly, who could have predicted this— government taste for money-creation during the Covid era. Implied here is a return to the ‘70s period of stagflation, high inflation combined with high unemployment (we currently are experiencing only the first) set to last at least a decade.

And where do you think the government will want to direct investment? None of this, I’m sorry to report, is over yet. Plan accordingly.

4

An entire academic industry was built around the study of ethnic conflict, communal violence, non-state actor violence (jargon layered atop what amounts to simple homicide) yet the developed West is always curiously absent. It turns out no matter how many millions of dollars you pour into research institutes to collect data it will only make their spotlights stronger, not wider, and they’re pointed quite far away. BJP riots in India get more headspace in the American media than protracted, but low-level, inter-ethnic violence on our soil, unless we can spin it into the first-coming of the Fentanyl Messiah. Clever commentators will point out that our ethnic conflicts aren’t really about ethnicity— this is true, and it’s true of all ethnic wars. Outside of being an utterly impoverished country, the variable (operationalized in a dozen different ways) most often associated with civil war is ethnic diversity. On the ground, the ‘explanation’ is always different and takes on the picture of a coherent ‘ethnic war’ only when aggregated. If there’s a sudden epidemic of black men pushing 90-pound Chinese women in front of oncoming trains, is that “because” of ethnicity? Who knows, maybe it’s a mental illness problem? (See: section 1 above).

Hey Evil,

I hope you are well! I was very sorry to see that you were suspended from twitter. Twitter though now dedicated to free speech seems to still get nervous reactions when the core constituency of the regime, white PMC liberal women, feel attacked. Poking the eye of Sauron in this case is a dice roll and you, unfortunately for all of us, got poked back.

I (and probably many others) are wondering whether you plan to resurrect/fight the ban/both or your general poasting plan. Not having a twitter account probably gives you much free time to do other things, so its understandable if you decide not to return.

Even if you do decide not to return, I think that you should request (if possible) an archive of your twitter data and post on here what you consider your best tweets/threads. It would be a real shame if what you wrote is lost to time and fated to remain undisturbed in a server somewhere in CA. Unlike the pyramids which were pretty well preserved, digital data is more unstable.

If you want to continue this conversation in private, my email will be in the next comment. I did not know how to contact you other than on here.

Looking forward to hearing from you!

William