Giorgio Agamben offers us a useful way to conceptualize postmodern totalitarianism. Like many brilliant concepts—such as Max Weber’s ideal type of the ‘state’—it condenses so much that to grasp its insight one needs to thoroughly unfold and expand it. I will do just that.

I will take a roundabout approach and:

Outline the ontology of ‘civil war’ (for my friends on the left side of the bell curve, this just means ‘what civil war is’ and ‘what it is like’)

Using (1), expand on Agamben’s definition of totalitarianism as a kind of civil war

Using (1) and (2), tackle myths about totalitarianism, such as the notion that ‘democratic totalitarianism’ is inherently contradictory

And, with (1), (2), and (3), argue that it is perfectly reasonable to consider the United States a totalitarian regime

To start with a confession, political scientists seldom write about ‘totalitarianism’ anymore. They have a dozen typologies of ‘authoritarian regimes,’ or ‘autocracies,’ or other non-democracies they purport to measure in increasingly sophisticated ways to obscure their neglible progress since the 1930s. Mentally retarded academics like Jason Stanley, who suffers from Down Syndrome and drafts his book manuscripts in blunt colored pencils, skip ‘regimes’ altogether and harange us constantly about ‘fascism.’ Yet, totalitarianism is a concept that has completely penetrated our collective imagination. Political scientists ignore it while speaking its language much as autistic psychologists (*cough* Bo Winegard) deride Freud while unwittingly plagiarizing him on a near daily basis. The standard retort is that ‘totalitarianism’ is difficult to measure, hence ‘unscientific.’

I have a different interpretation. Academics have discarded the concept of totalitarianism because, on some level, they are dimly aware of its implications. In fairness to them, it’s the sort of thing one could be forgiven for not wanting to know. . . .

I. What is a Civil War?

Totalitarianism is a kind of civil war. What is civil war? Perhaps you picture the American civil war, a symmetric conflict the likes of which no longer exist, or an insurgency like those experienced in Iraq or Afghanistan. Either mental representation probably involes blood-stained battlefields as two unitary sides compete, in direct fashion, for victory. This conceptualization of civil war, however, is fundamentally flawed.

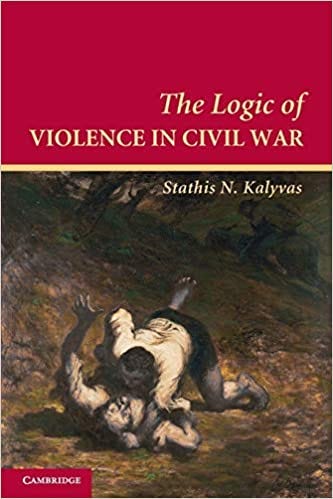

To understand civil war, let us turn to Stathis Kalyvas’ book The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Put aside that Kalyvas is an academic snob, is probably gay, and certainly has a gay European name—his is perhaps the only political science book written this century (including my own) worth reading.

Since Kalyvas is certainly too gay to have fought in battle, he did the next best thing. Between jerking off in the dank, unlit corners of the Yale University Library, he read mankind’s collective works on civil war. Not ‘studies’ where an underachieving political scientist managed to chew his keyboard until logit civil_war GDP, robust appeared in Stata, but the primary sources: personal wartime accounts written by soliders and generals, ethnographies written by anthropologists who lived in wartorn regions back when they had balls, every civil war history rich in primary sources. You have to give him credit: he’s one of the few academics who actually did his job.

What he found were similar patterns in the conduct of civil wars across time and space, ones that upended the traditional model of civil war. Most violence in civil wars does not take place in battle or on the frontlines.

His model of civil war, shown below, seems complicated but is quite straightforward. I will spell it out for us crayoneaters.

In civil war, you have two sides—the state and insurgents—fighting over territory.

Let us divide territory into five zones: zone 1 is complete government control, zone 3 is the contested zone (frontlines), and zone 5 is complete insurgent control.

You will notice that governments kill the most within their own zone of control, and insurgents likewise murder most in areas where they have control.

Why? This does not make intuitive sense. It turns out each side murders people under its control not only because it is easiest, but to prevent ‘their people’ from defecting to the other side.

They use selective violence by executing ‘defectors,’ ‘rats,’ ‘informants,’ or ‘double agents.’ In other words, they show people under their control, “look, if you cross us we will find you and we will murder you!”

How do they find these victims? They receive denunciations. And here is the dishearting part, the revealing part about human nature: people will denounce each other as “traitors” to evil states or insurgents for petty reasons, to settle a score, to punish a rival, to gain an advantage in love or career, to discard of a no longer needed friend or relative. Neither states nor insurgents care whether the accusation is true, so long as witnesses perceive that speaking out will result in death.

While much violence is carried out by states and insurgents, often the locals are intimately involved themselves. . . .

Does this sound familiar yet? Do not worry, it will. And if you remain skeptical, I encourage you to read Kalyvas’ book.

II. How is Totalitarianism a Civil War?

Totalitarianism is a one-sided civil war. It is a civil war where one side has absolute control over the territory it claims. We might think the imposition of state power—Leviathan—brings peace, but recall that in civil war a state commits most its violence in areas it controls. Now that’s the whole country. Congratulations, peace at last.

States like power, so why should they tolerate ‘defectors’ or ‘traitors’? After all, they can impose a great “or else!” over their subjects by punishing perceived ‘traitors.’ And it turns out that people are quite willing to denounce their friends and neighbors to a totalitarian state when it serve their interests.

Kalyvas gives the example of Pavlik Morozov, who denounced his father to the Soviet Union for strictly personal reasons, a fact the Soviets ignored because they could hold Pavlik up as a exemplar Soviet who put state before family.

We see this everywhere in totalitarian regimes. In Nazi Germany, spouses were the largest source of denunciations to the regime. Or take the Cultural Revolution, where people were free to murder their neighbors to steal their land so long as the CCP could claim the victims were ‘class enemies.’ It was not the state or the Red Guards who carried out the atrocities in this case so much as embittered associates, all under an state ideology that legitimated their perversities. (Quote below is from Yang Su’s book Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution).

Totalitarianism operates according to the same logic as civil war. A state, now with absolute control, wants to root out ‘traitors’ to feed its inherently expansionist nature and associated need to demonstrate power. With a legitimizing cover, many people are more than happy to denounce their competitors to the state or, when given tacit approval, to eliminate their rivals themselves. Agamben is correct to describe this as ‘legal,’ in the sense that the state sanctions civil war against its enemies.

III. Myths of Postmodern Totalitarianism

Does totalitarianism necessarily conflict with democracy? Or is it simply that they tend not to occur together? Scholars of civil war observe that internal wars are rare in democracies, but they certainly do not claim civil wars cannot happen in democracies. Totalitarianism is a form of civil war. I presume you can connect the dots, unless you are a political scientist.

I have already covered the nonsensical ‘science’ of democracy measurement. What is happening here is a more rudimentary error: the asinine logical contortion that because we are [good thing], we cannot possibly be [bad thing].

Thoughtless social science aside, did civil war become obsolete in the Western, democratic world, or did it merely change form? Certainly the United States has not suffered from another cataclysm like the civil war. It nonetheless experienced serious periods of tumult and political violence, such as the 1960s and ‘70s where terrorist bombings were frequent, riots were common, racial tensions were at an all-time high, and the murder rate soared. Or was that 2020? Sometimes it’s hard to remember.

I will not deny that these ‘postmodern civil wars’ are less devastating than the ‘authentic’ versions. Yet, they are still political violence and still devastating, especially when you account for the skyrocking murder rates. Kalyvas makes clear, even in ‘real’ civil wars most of the violence is homicidal in nature, rather than the mental image we hold of duelling armies. Our simulated civil wars have more in common with ‘real’ ones that the measurement whizzes would have us believe.

If civil war can change form in developed, Western countries, then perhaps totalitarianism, as its natural outgrowth, also takes a different shape. It occurs wherever people denounce each other based on a state sanctioned ideology that grants their betrayals legitimacy. It is not necessary that the President bellow, megaphone in hand, that this is accepted: it will allow these denunciations when it serves its interest of signaling to witnesses, “or else!” And it will staff the country with a decentralized network of ears—commissars, Red Guards, Stasi, human resource officers, et cetera—to whom people can denounce their rivals.

I lost my train of thought. I will leave final word on this issue to history’s faggiest Frenchman.

Curious that totalitarianism is considered incompatible with democracy.

But one more myth. What is absent from the conceptualization of totalitarianism thus far? So often it seems we cannot possible live under totalitarianism because, unlike Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, or China during the 1960s, we have no ‘great leader.’ This is irrelevant. Totalitarianism is obviously more visible with a madman at the helm, hence a totalitarianism that was specifically meant to conceal itself—a postmodern totalitarianism—would not have one. All the mechanisms are identical, with no leader to point to as responsible and an ideology that remains untethered to any one man.

IV. The United States is a Totalitarian Country

I am drunk and tired and you do not need me to connect the dots. I am not yet prepared to write a sprawling condemnation or genealogy of Woke. You know who denounces, for what purpose, to whom, why it’s sanctioned, and how it’s perceived. When even affable robots take notice with ease, I will assume appeals for ‘elaboration’ are in bad faith and respond with a resounding, Derridean “no.”

One reasonable retort is, “what of the fact that totalitarianism is the culmination of civil war, its final stage?” To that, too, the answer is transparent: you slept through the civil war.

To the inevitable question of “what next,” political scientists have, in their infinite bumbling, discovered that mountains, what they call ‘rough terrain,’ make it difficult for a state to persecute you, although whether that holds true in a postmodern, technological landscape is questionable. With postmodern methods, a postmodern strategy of “exit” is required.

I am not saying that the United States is an absolute, incorrigble totalitarian regime. I am merely providing a framework for understanding the current political situation since so few are to be found. It is not “true” or “false,” but “useful” or “useless,” which is a conclusion each must reach for himself. Be prepared

It's interesting that, from a long term perspective, the regime ran an effective, totalitarian operation, with the movement of peoples, lower wages, the semi-controlled mayhem to break up and prevent livable urban areas. However, since the Bad Orange One came on the scene, they've lost their touch. They do cruel half measures now, like persecute some MAGA journalist or brutalize some yokel who sat at a desk in the capitol. Many cases of bizarre, seemingly counter productive, or badly half-assed projects/operations. Maybe they think they are 'encouraging the others', but Lenin never took half measures. It seems they are determined to make millions of people hate them, but not to immediately destroy those people. Strange.

There are many post-modern totalitarians around... and not a few good old fashioned totalitarians. But they are not a majority in the USA, and even as we speak there is pushback against them. It is even possible that conservatives have learned something in recent months and years, and will use power more effectively when take control of Congress in 2022. Maybe.