Evil Weekly (10/10/2022)

1

Any decent political science PhD program will start with a course on the philosophy of science, after which you are pulled aside and the instructor whispers into your ear, “none of this applies to social science.” Of course, neither of these happen today. Why this is true is the subject of a much longer post, but it’s true nonetheless. You could discuss the trajectory of contemporary social science through the language of Kuhnian paradigms and make it superficially sensible. In International Relations, the Realism of someone like Samuel Huntington (his Clash of Civilizations thesis is merely Realism scaled up to a higher unit of analysis, the civilization) represents an older paradigm that formalizes intuitions about Great Power Politics. ‘Normal science’ within this paradigm proceeds as, I don’t know, historical case-study analysis. By the time Clash of Civilizations was published, we saw a turn to a new paradigm: rationalism (in the economic-rationalism sense). A more important change, concurrent with and likely accelerated by the turn to rationalism, was the ‘normal science’ practice of testing all your theoretical implications with regression analysis.

But the analogy breaks down. In the article that elevated rationalism to a ‘paradigm’, the author writes: “What I refer to here as ‘rationalist explanations for war’ could just as well be called ‘neorealist explanations.’” Realists agreed, and were a bit grumpy that rationalism merely repackaged their theories inside a tighter, game-theoretic box. It’s not so much that the paradigm changed than ‘normal science’ changed due to generational turnover in the field. What inconsistencies or unexplained phenomena caused IR to put aside Realism? Nobody knows. What new predictions did rationalism make? Nobody knows. As I pointed out last week, every time a rationalist decides to make a prediction— which is rarely— it turns out wrong. And despite tens of thousands of regression analyses, I have found a grand total of one article on interstate war that evaluates its models out-of-sample (its point, of course, was to show political scientists a new ‘method’— point taken, throw it in the regression tricks toolbox. What do you mean there’s no Stata package for it?) It’s normal science for the sake of tenure, and the normal science isn’t even good.

All this hides an even bigger change. After the Cold War, everyone decided that Great Power Politics was immediately irrelevant and to study ‘democratic peace’ and ‘international institutions.’ But one can only put ‘dyadic democracy’ in so many regression models before that research program gets stale (it turns out that’s still hundreds of regression models, each with minor tweaks that amounts to statistical noise). Not to mention that you don’t need a PhD to realize Canada, US, Britain, and France haven’t gone to war with each other since WWII. A map and upper-double digit IQ will get you there. Old, stodgy Realists were quick to point out that American hegemony (in their language, ‘unipolarity’) was the omitted variable but that didn’t much matter. It didn’t matter because by that time International Relations had decided not to study International Relations.

You read that right. Somewhere between the Balkans and 9/11, and accelerating afterwards, IR scholars decided the threat of interstate war was so marginal that they didn’t need to study it all. All that was left to worry about was civil war, which had the nice benefit of fitting within the field’s newfound methodological niche (it’s easier to do micro-level econometric analysis and think up plausible sources of exogeneity between tokes at lower levels of analysis). Once in awhile someone would be hired to write bigthink books about the rise of China, but generally there was no grant money / interest and, besides, if you wanted to study interstate war you would be behind your peers methodologically— attacked from both sides. Even if you are blessed to know nothing of this cursed field, you’ve probably heard John Mearsheimer’s name. You probably didn’t know that his students can’t get academic jobs. Seriously, they ship them to Abu Dhabi. On top of that they don’t know math— I have had the misfortune of interviewing Harvard IR PhDs who nobody will hire to teach and breaking it to them that, yes, they must know what a for-loop is to get a coding job— so they are fucked from all angles. There is no incentive for young IR scholars to study the one thing the field was invented to study.

Oh, but they will certainly pretend to be experts once WWIII rolls around. Do you remember when 9/11 happened and all the IR profs said, “leave it to us” and we had 10,000 regression articles on terrorism that nobody remembers and all we have to show for it is an FBI that knocks on your door for liking too many jigaboo jokes on Twitter. You will hear from the experts when conflict breaks out— we’ve seen no shortage of that already— but the fact is there are no experts in interstate war any longer. A wise country would listen to a bored Google software engineer who reads history books because his job only requires him to code 5 hours a week. Don’t roll your eyes, it’s deliberately designed this way— for decades the IR establishment proclaimed their own field superfluous. Well?

To close the circle, the old theories were discarded because theories, except in an implied sense, were discarded. Sure, some will pretend to be social constructivists but, push come to shove, they can’t articulate its tenets; what they mean to say is they want to run regression analyses with ‘has vagina’ as an independent variable. A consequence is that when someone tells you the old theories are wrong, what they mean to say is “we don’t do that anymore.” Why? Nobody knows. It certainly isn’t because they were shown to be wrong in any meaningful sense. Perhaps the theories were vaguely racist. Who knows. Now there’s a war in Ukraine. Who could have predicted this? Maybe of the art of theoretically-informed prediction is a battle that barely lives on in the heads of 80 year old men. Good thing we don’t do that anymore.

2

Another post on how ‘data availability’ does not translate to ‘data transparency.’ Inconvenient facts, like who commits most the homicide, are erased or left unpublished while others, like MCAT scores, will be quietly re-scaled with the details hidden inside the footnotes of an appendix stuck ten layers deep on a website that looks like it hasn’t been updated since Bush. You will have to look very hard to see the raw data, but not to see this trend in action—

3

My second ~20 percent short on Tesla. I probably could have let this position run awhile, but they’re called “short” positions for good reason— bear market rallies can eliminate paper gains quickly and leave you waiting months to recovery (see: the June to August rally). Together, this leaves me with an approximate 40 percent gain on Tesla shorts even though it’s only down about 15 percent since January due to the high volatility. That’s one short rule I never break (another is, no matter how concentrated your short positions are, never make a single one a sizeable portion of your portfolio: 2-3 percent seems fine, 5 percent verges on excessive). But atypical markets signal that the ordinary rules— the ones that operate smoothly 85 percent of the time— no longer apply and you need to think creatively and nimbly. One rule I broke here is to never short a company I don’t believe will ultimately head toward irrelevancy. My best shorts from the first half of the year— UiPath, Duolingo, Netflix, Wish— are companies whose products I experimented with and determined to be utter garbage destined for the grocery store bargain-bin. I have never driven a Tesla. All I know is this: the valuation is incredibly rich and they’re just cars, bro. Couple the price with inflation and the fact that longstanding car companies can reverse engineer whatever Tesla does and it’s an obvious short candidate. I knew this from Netflix— it doesn’t matter how many uber-autists build your recommender systems if the selection of movies you have to recommend is terrible and you can crowd fifty people on one account. An added benefit is I believe it’s desirable that Tesla’s stock craters. Elon will be forced to incrementally liquidate his holdings while they’re still inflated and I pray he shovels the cash into SpaceX (whatever is left over from Twitter, I guess). We need humanity on the moon; we don’t need upscale electric cars for a bunch of San Francisco queers who won’t be able to keep up with the payments once their AI-powered vibrator startup goes under.

I will short Tesla a third time if it rallies again (but not if it tanks all at once or continues to trickle downward). I anticipate that the current bear wave will continue till about SPY equals 330 (plus or minus 15) before we see another substantial rally (20 percent bounce off the local bottom). If this obtains, I’ll close out more short positions along the way. Otherwise, if the market rebounds sharply, I’ll start piling cash back into shorts— we aren’t getting out of this recession that easily.

4

Relatedly, I read Mark Spitznagel’s Safe Haven Investing this week. Solid read. While most investment books are little more than simple arithmetic, Mark’s book is simple arithmetic and a dose of philosophy 101. This is good. Most investment strategy writers come across as moderately numerate dummies, which is appropriate should you need a bespectacled, older buddy to remind you to max out your IRA contributions and wash your balls à la Jordan Peterson. Unless you are a completely passive investor and just want to grill— that’s probably fine, since not everyone has broad interests, though I would caution that whatever you treat with inattention will crumble given sufficient time— personal finance is less a game of mathematics than it is an epistemology that wraps logic and probability theory inside it. Certainly a grasp of the mathematics is necessary, but that achieved I’d much rather read from someone with a wide enough set of experiences (personal and vicarious) and interests to articulate a non-trivial vision that the math serves. Foxes beat hedgehogs in the long run. Some people manage to leave their epistemological assumptions implied and come out wealthy. It worked for the boomers. Perhaps it will work forever.

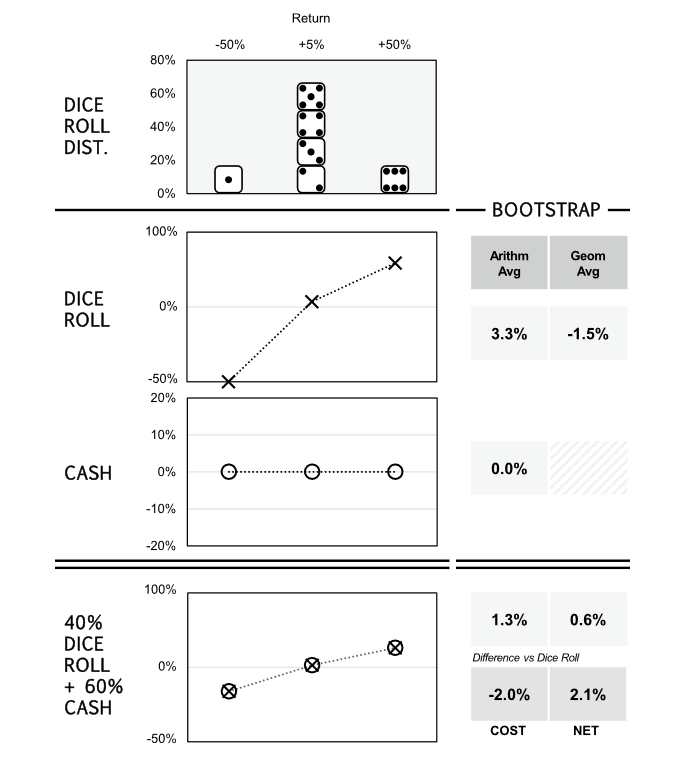

Mark’s book revives the geometric mean maximization theory of investment. This would only sound familiar if you’re in the habit of reading old works since it was sidelined since the ‘70s (like many theories, perhaps the reasons it became unpopular have nothing to do with its theoretical contents). It traces the idea back to Daniel Bernoulli’s writing and claims its investment strategy as the latest in this tradition. The idea is simple enough, illustrated in this figure:

Clear and concise (in case it’s not intuitive why you ought to concern yourself with the geometric average versus the higher arithmetic average, recall the latter is ‘non-ergodic’ or, in straightforward language, the mean value of any realization of the dice game in the top panel over n iterations is substantially higher than its median. The book has a second version of this figure where instead of cash reserves the player stakes a small amount in insurance— hopefully you see where that’s going). You may also recognize the similarity to the Kelly criterion, names after John L. Kelly (a man after my own heart, he worked at Bell Labs, made contributions to a number of fields, then died at age 41 because he smoked up to six packs of cigarettes a day).

But again, the mathematical components of his strategy are not revelatory. What’s more interesting is Mark seamlessly joins the math, philosophy of science, history, and his love of Nietzsche into a workable general theory of investment. Of course, this means you will not find easily imitated tactics or recommendations on where to stick your money this moment. If you’re anxious for these tips, you picked the wrong game; stick to index funds. I don’t think the breadth of the author’s interests are unrelated to his success as a hedge fund manager. Autists aside, and even including some autists, many of the most successful investors are Berlin’s foxes because smart people don’t normally close off entire domains of knowledge and because, at any rate, ‘finance’ isn’t a singular, self-contained science like physics. Burry was a medical doctor, Icahn a philosophy major, even uber-boomer Munger studied math, meteorology, and law. Your MBA ‘loves balance sheets and football’ broker isn’t worth the fees. Back to the index once more.

Miss the substack :( Anyways, to add to your list of investors, Alex Karp ran an investment office (built from a $1m inheritance) while being a research associate at the Sigmund Freud Institute and after doing a PhD at Goethe Univ